Bianca Maria Piraccini

1. Dermatology Unit, IRCCS Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Bologna

2. Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences University of Bologna, Italy

Introduction

People with skin of color come from a wide range of racial and ethnic backgrounds. Unfortunately, there are significant disparities in dermatologic health among these individuals leading to insufficient physician training and a lack of high-quality research focusing on skin conditions that affect people with skin of color. In the realm of hair disorders, there a few conditions that predominantly affect people with dark phototypes.

Frazier, W. T., Proddutur, S., & Swope, K. (2023). Common Dermatologic Conditions in Skin of Color. American family physician, 107(1), 26–34. - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36689965/

Traction Alopecia

Traction alopecia (TA) is a variety of mechanically induced hair loss that develops when certain hairstyles exerting a constant pulling force on the hair. It is frequently associated with Afro-Caribbean hairstyles involving tight braids. Its onset often occurs in childhood and may initially be reversible. TA has in fact a two-phase nature, with an early, non-scarring, and reversible stage, progressing to a scarring and permanent condition in chronic cases.

Balazic, E., Hawkins, K., Choi, J., Konisky, H., Chen, A., & Kobets, K. (2023). Traction alopecia: assessing the presentation, management and outcomes in a diverse urban population. Clinical and experimental dermatology, 48(9), 1030–1031. https://doi.org/10.1093/ced/llad154 - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37098178/

Data from South Africa shows that TA affects both children and adults. Among adult women, up to one-third (31.7%) experience hair changes, and in children aged six to 15, the prevalence ranges from 8.6% to 21.7%. Among African American girls aged 5.4 to 14.3 years, 18% show signs of TA. It's more common in African schoolgirls than boys (17.1% vs. 0%) and in females compared to males (31.7% vs. 2.3%), with affected men often wearing cornrows and dreadlocks.

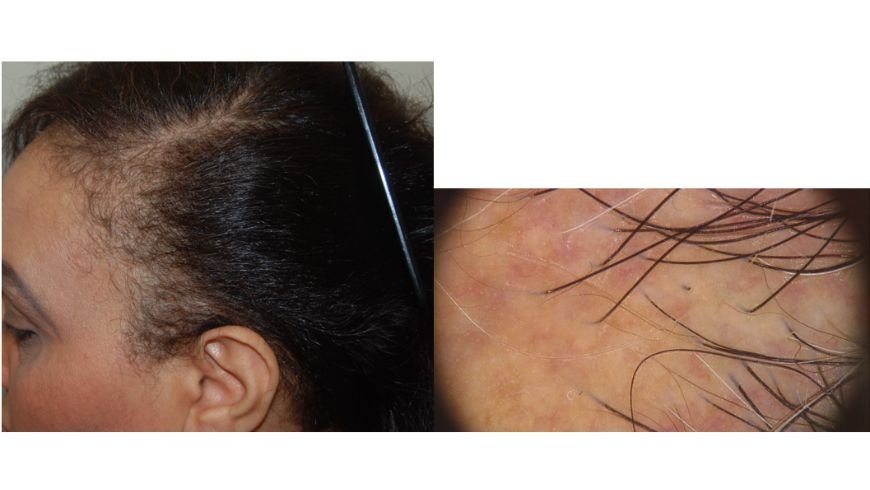

Hair loss usually starts in the temporal, preauricular, and above the ear regions but may extend to other parts of the scalp, particularly in cases where "cornrow" patterns are adopted (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Clinical and trichoscopy pictures of traction alopecia of the temporal region. The hairs are broken at different length and trichoscopy shows thin hair and a black dot due to hair brackage.

Other findings may include folliculitis, hair casts, reduced hair density, replacement of some hair with vellus hairs, and occasionally broken hairs in affected areas, leading to scarring alopecia. TA can also be associated with headaches, which are relieved when the hair is loosened.

Pulickal, J. K., & Kaliyadan, F. (2023). Traction Alopecia. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29262008/

Figure 2. Clinical and trichoscopy pictures of a long-lasting traction alopecia of the hairline. The hairs are broken at different length and trichoscopy shows reduction of the hair with permanent alopecia and thin hair.

The treatment approach to TA depends on the stage and chronicity of the disease, as well as the presence of permanent alopecia. Treatment strategies can be divided into three stages: prevention, early traction alopecia, and longstanding traction alopecia. In the prevention stage, education is crucial for parents, children, adolescents, and young adults regarding proper hair care practices. In the early traction alopecia stage, where follicular units are still intact, the focus is reducing hair tension by adopting hairstyles that minimize braid tightness. Topical or intralesional corticosteroids are recommended if there is evidence of inflammation, such as scaling, erythema, or scalp tenderness. For longstanding disease, surgical options are viable. Hair transplant techniques like micro-grafting, mini-grafting, and follicular unit transplantation have been found effective. Additionally, a novel therapy involving alpha-1 adrenergic receptor agonists has been explored for managing traction alopecia. These agonists induce contraction of the arrector pili muscle, increasing the force required to pluck the hair. Topical phenylephrine, a selective alpha-1 adrenergic receptor agonist, has been tested and found to reduce hair loss secondary to traction in female patients.

Balazic, E., Hawkins, K., Choi, J., Konisky, H., Chen, A., & Kobets, K. (2023). Traction alopecia: assessing the presentation, management and outcomes in a diverse urban population. Clinical and experimental dermatology, 48(9), 1030–1031. https://doi.org/10.1093/ced/llad154 - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37098178/

Pulickal, J. K., & Kaliyadan, F. (2023). Traction Alopecia. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29262008/

Central Centrifugal Cicatricial Alopecia

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA) is a common form of scarring alopecia primarily affecting the crown or vertex of the scalp, leading to permanent hair loss. While the exact cause of CCCA remains uncertain, potential risk factors include genetic predisposition, autoimmune diseases, infections, and other idiopathic factors. Seborrheic dermatitis (SD) has been identified as a common concurrent hair disorder in patients with CCCA, particularly in African American women. This suggests a possible connection between SD and other inflammatory scalp conditions in this population.

Okwundu, N., Ogbonna, C., & McMichael, A. J. (2023). Seborrheic Dermatitis as a Potential Trigger of Central Centrifugal Cicatricial Alopecia: A Review of Literature. Skin appendage disorders, 9(1), 13–17. https://doi.org/10.1159/000526216 - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36643200/

Clinically, CCCA begins at the vertex scalp and expands centrifugally in a regular or pactchy way, with loss of follicular ostia as the disease progresses (Figure 3). CCCA is most prevalent in women of African ancestry, typically starting in their late 20s, and is rarely seen in men.

Lubov, J. E., Okereke, U. R., Clapp, B., Toyohara, J., Taiwò, D., Kakpovbia, E., Lo Sicco, K., & Adotama, P. (2023). Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia in Black men: A case series highlighting key clinical features in this cohort. JAAD case reports, 38, 27–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdcr.2023.05.026 - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37600725/

Sloan B. (2023). This month in JAAD case reports: October 2023-Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia in Black men. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, S0190-9622(23)02423-4. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2023.08.002 - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37562602/

Historically, certain hair care practices such as the use of hot combs, relaxers, braids, weaves, or tight extensions have been associated with CCCA, although conclusive evidence supporting these associations is lacking. Recent studies have linked CCCA to a mutation in the gene that encodes peptidyl arginine deiminase, type III (PADI3), an enzyme involved in hair shaft formation.

Figure 3. Clinical and trichoscopy pictures of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: cicatricial alopecia at the midline portion of the vertex scalp with loss of follicular ostia at trichoscopy and peripilar white or gray halos.